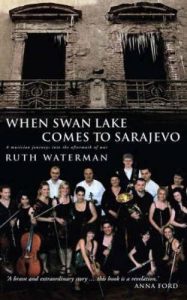

When Swan Lake Comes To Sarajevo

A Musician Journeys into the Aftermath of War

Canterbury Press

The Strad

A Book of the Year – The Observer UK

War is always with us, and so is peace. This book is about the peace that comes after a war. It is one woman’s account of her experiences in the new country of Bosnia as guest conductor of a remarkable little orchestra, the Mostar Sinfonietta.

International violinist Ruth Waterman first met the musicians of the multi-ethnic ensemble in 2002, and since then has returned regularly to the region, teaching, conducting and performing, and listening to their stories. Here she describes the nuts and bolts of daily life – in turn frustrating, hilarious and touching: the putting together of concerts despite the odds; the rebuilding of bridges, towns, communities, lives; and how making music can connect us to our essential humanity and to each other.

Ruth Waterman’s writing is humane and down-to-earth, perceptive and inspiring. Interspersed with her diaries and observations are the stories of war and peace by the Bosnians themselves, in their own voices, acts of witness that reveal their courage, despair, resilience and humour.

This intermingling of narrative and first-hand accounts builds a mosaic that provides a visceral introduction to an unfamiliar world where people simply want to ‘live a normal life’.

This book by violinist, conductor and poet Ruth Waterman [is] inspiring … she captures the humanity of the place and its people: the pain, the resilience and, yes, the humour.

Classic FM Magazine

I had never been to a post-war country before, though I’d often wondered what happens after the guns are silenced and the media moves on. Encountering Bosnia as a musician rather than as a diplomat or social historian or journalist, I didn’t know how to understand the long uncharted path away from the days of violence.

This is an account of my personal journey, of my experiences and thoughts in the order in which they happened, with all their incompleteness and contradictions and misunderstandings. In a chaotic country, one experience after another piles up, feelings sometimes follow facts at a remove, and the sense of it all emerges only gradually, if at all. In choosing to write without the benefit of hindsight, I have attempted to give a flavour of what it was like to walk in the aftermath of war, to breathe the Balkan air.

At first there was a vague thought of making a radio programme (which was in fact broadcast on BBC Radio 4), so I took a tape recorder in case people wanted to tell me their stories. I was startled, and touched, by the number of acquaintances and strangers who, without invitation, started to talk of their experiences both during and after the war. It seemed part of a deep need to speak, to have someone hear them, especially an ‘international’ as I was called. What they said was so extraordinary that I continued to record them during my subsequent visits. So this book honours the victims and survivors of the Bosnian War by having them speak in their own words, opening an invaluable window onto how a people survive catastrophe, and by inference, how we all survive and live our lives.

Ermin

And then they destroyed apartment more than before. Yes we were here, all the shells come, in this room three shells coming. And it was funny things, in this period of course I was member of the army. And I’m coming home to sleep. And I slept overnight, we put this big cabinet in the window to protect us here in this corner. In the morning my wife told me ‘why you didn’t take all the bullets from your pockets?’

I said ‘what you talking about?’

She said ‘look, all these bullets are all around the room.’

But that’s coming from window, and we’re sleeping! From the Gymnasium, machine gun bullets. We sleeping all night and we didn’t know! My wife she thought I have in my pocket bullets from gun. And she start to collect these bullets from room and I say these are not my bullets and we find out there’s hole in our cabinet. Put on the window to protect us. All night it’s very loud, grenades and everything, so, so. But this is the kind of protection of body you going to sleep, you don’t like the situation and you going to sleep and forget about everything.

********************************************

Dress rehearsal. The bassoonist, who could not come to any of the other rehearsals, is nowhere to be seen. I start without him, and we have just finished rehearsing the Adagio when he walks in, an hour late, and seats himself in the empty chair.

At the break, he comes up to me and apologises for his late arrival. He is tall and dignified.

‘My wife was driving,’ he explains.

I’m speechless.

‘She drives slowly,’ he adds, as if this clarification makes his case indisputable.

Many replies jostle in my brain, but as I look up into his lined face, I just nod. Or maybe I shake my head. Or maybe I smile. I’ve no idea anymore. As far as excuses go, this is one of the best.

*******************************************

This first visit to Bosnia left me with many strong memories. The location itself, with its bullet-riddled walls and collapsed buildings, was a new experience for me. As was making music in such surroundings. Music goes anywhere, but here it was in its element, touching raw emotion, going straight to the heart. I have played the same Mozart Adagio in the Hermitage in St Petersburg, a splendid palace with room after room of magnificent works of art. These two places stand at opposite poles of human activity, and the music filled the space in different ways. But I felt the same connectedness to the Russian people, setting aside their daily lives for the moment to come together in Mozart, as I did in Bosnia, we who were playing, and those who were listening, brought together into a temporary community, the sounds vibrating through us all simultaneously.